Autumn-Winter Quarterday - Samhain

Festival of Peace

Beginning of November

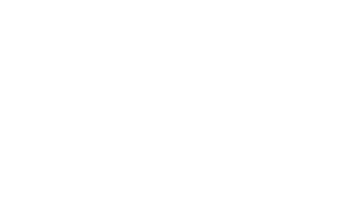

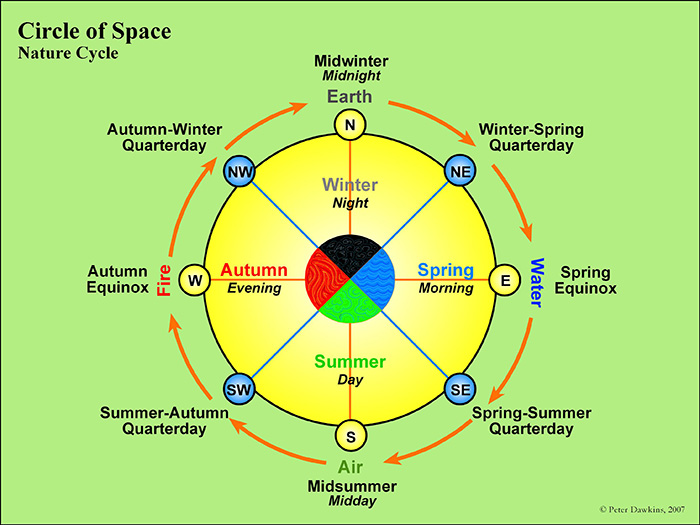

The autumn-winter quarterday marks the cusp of autumn and winter, when autumn ends and winter begins.

In Celtic countries this festival is known as Samhain (‘Fire of Assembly’). It is the Festival of the Dead or Festival of Peace, and the fires for this festival are peace fires lit in thanksgiving, not only for the harvest (which has now finished), but also for the whole year, and for all friends, family and ancestors, and for the Sun-god, Hu or Ies-Hu, who dies at this time. It is the third and last of the three harvest festivals, and marks the completion of the year's work, and the start of a time of rest or peace leading up to the birth of the new year and Sun-god at the winter solstice.

Because it is the last harvest of the year, it is also the time of threshing and winnowing, during which the grain is separated from the chaff. The chaff is then burnt in the Samhain fire, releasing light and warmth from the flames. The symbolism of this is used in the stories of Bridget and Persephone, each of whom is consumed in fire as she gives birth to her child of light, the new Sun-god. Thus, just as the old Sun-god dies, so does the goddess – all in order to give birth to the new. Thereby all nature renews itself, over and over again.

Christianity named the three-day festival of Samhain as All Hallowed Eve (Halloween), All Hallowed Day (All Saints Day) and All Souls Day. The original idea underlying this was that on the first day the wise ones, the illumined sages or huicca (witches),* were honoured and thanked; on the second day the saintly souls were honoured and thanked; and on the third day all other souls were honoured and thanked. In order that the thanks can be properly given, the souls concerned and their deeds have to be remembered.

The Christianised pre-Christian Martinmas (11 November) also celebrates this final quarterday of the annual cycle, St Martin being the end-of-harvest saint who was metaphorically cut up and eaten in the form of an ox. In the Christian story of Jesus, this festival corresponds to the Last Supper, and the Crucifixion and Entombment of Jesus (although the actual historical events took place at another time of the year). The ox is symbolic of the Hebrew letter Aleph, Greek Alpha, signifying the divine Creator. It also signifies the Creator's Son/Sun, as in the classical Dionysian myth and the Egyptian Horus myth.

From the very last sheaf of corn (called the ‘neck’) from the last harvest of the year is made a type of corn-dolly known as the neck corn-dolly or hag, representing the goddess who has now given birth to her child. This is kept for good luck (i.e. fertility) in the next annual cycle, symbolic of passing on the best of the old into the new, so that nothing truly good is ever lost and the cycle of life is smoothly continued.

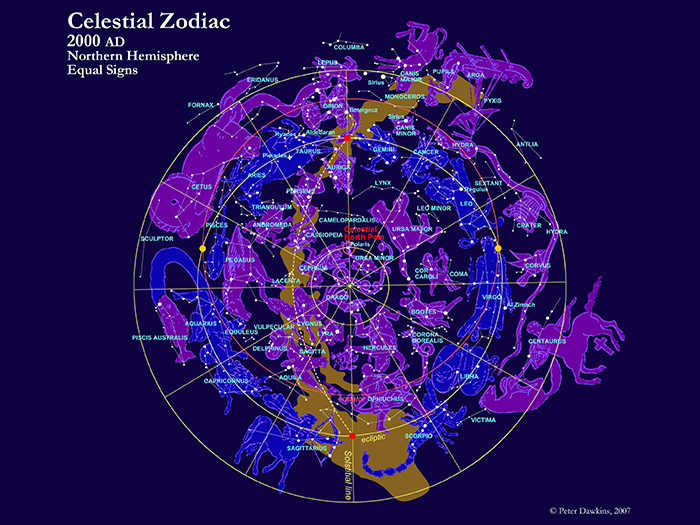

In terms of the gateway that this festival represents (i.e. the gateway from autumn to winter), its archetypal gatekeeper during the last Age was the eagle-faced Cherub, associated with the zodiacal sign of Scorpio. Now, in the new Age that the world has just entered, due to the precession of the Sun, it is the Cherub of Libra who stands in this position.

© Peter Dawkins

- Zodiac of Ages

- The Great Ages

- The Phoenix Cycle

- The Solar Breath

- The Grail Cycle

- The Great Festivals

- Solar Festivals

- Winter Solstice

- Winter-Spring Quarterday – Imbolc

- Spring Equinox

- Spring-Summer Quarterday – Beltaine

- Summer Solstice

- Summer-Autumn Quarterday – Lammas

- Autumn Equinox

- Autumn-Winter Quarterday – Samhain

- Lunar Festivals